A Journey to the Rugged Ends of the Earth

On the Search with South American slab hunters Bruno Santos and Guillermo Satt.

“We are in the middle of the Pacific, on a volcanic rock, getting bludgeoned by massive swells. We are, as remote, as you can get.”

That’s Australian photographer Ted Grambeau talking. If you know Ted Grambeau, then you’ll be able to hear the sound of his deep, rough, vaguely erratic voice; the volume rising with each syllable, the delivery slowing with each word, dragging out each sentence until you can almost feel their isolation.

“This place… the surf… it’s not for the faint-hearted. If we are going, we are going in search of some of the most hard-core waves you’ll find. It’s remote, it’s dangerous, and we will be on the edge. – Ted Grambeau

Two days before this vocal eruption, Ted called the Rip Curl head office. He said he knew of a place, and that place was about to get absolutely smacked with swell. The winds were right. The direction didn’t matter. The only thing that mattered was that it would be two days of travel, and the clock was ticking.

If the call had come from anybody else, another enthusiastic photographer looking to jump on a trip, the answer would have been no. But it came from Ted, and of all the world’s photographers, Ted is up there when it comes to knowing what the hell he’s talking about. He has spent the better part of the last three decades charting swells, staring at maps, and learning the ocean.

“We can’t just go taking anybody,” he said. “This place… the surf… it’s not for the faint-hearted. If we are going, we are going in search of some of the most hard-core waves you’ll find. It’s remote, it’s dangerous, and we will be on the edge.”

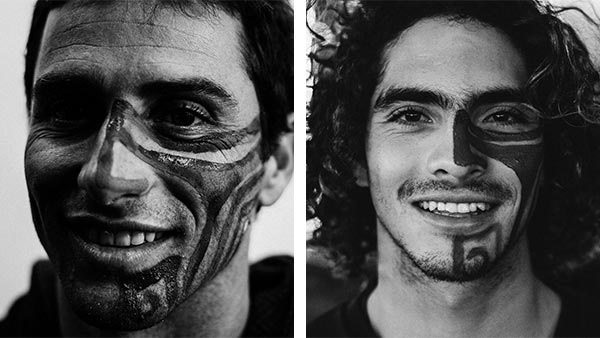

Two men from the Rip Curl athlete pool fit the job – 34-year-old Brazilian Bruno Santos, and 24-year-old Chilean Guillermo Satt. The two men have known each other for the past decade not only as Rip Curl teammates, but also as travel companions, having spent months together chasing heavy swells around South America and outer lying regions.

Bruno first made a name for himself in big wave surfing when he won Teahupo’o through an entry into the trials, and since then has continued on as a full-time Searcher, chasing heavier and more remote slabs with each journey. Guillermo, a full decade younger, is just beginning to follow in his friend’s footsteps.

So within 48 hours, Bruno, Guillermo, Ted and videographer Jon Frank were walking out of a tiny airport on a tiny island in the middle of nowhere. As they opened the doors they were met with a brisk wind and light drizzle. They shook hands with their connection, a local waterman who goes by the sole name Alemao, and embarked on the start of a journey navigating some of the most terrifying and rewarding waves of their lives.

“There was a huge amount of anticipation leading up to this trip,” says Ted, still recalling memories three months later. “It was almost like an eerie drama, because once you see the coastline you realise where you are. It’s probably the heaviest coastline I’ve ever seen surfed, and not user-friendly in any way.”

On one side of the island is a big, perfect bay outlined by a sheer cliff face diving into the ocean. A wave runs along the bottom of the cliffs, then turns and grinds across the bay. When it gets big it can be a 12-foot dry-reef slab, one of the best waves the boys found. Dwarfed by the surrounding volcanic mountain, it is a post-card perfect left.

“It doesn’t look quite as impressive until you put a human in there for reference,” says Ted. “The little dots on the hill that you think might be rocks are actually cows and horses. When you realise that, it dawns on you how big the swell really is. We quickly found out that six-foot surf was actually 10-12 foot, and absolutely reeling down the point.”

No matter how beautiful, the wave doesn’t come without a set of hurdles, and with them a set of consequences. The entry into the water is tricky, potentially deadly. “There’s a 20-foot cliff jump to get into the ocean,” Ted explains, “and then you have to get across the bay, which, if it’s big, can be completely closed out. Afterwards, to get back in, you’ve gotta somehow scale up that same rock face, timing your attack between sets. It’s crazy, and for experienced surfers only. There are a lot of guys on the World Tour, most, actually, who wouldn’t be comfortable out there.”

Couple the intemperate nature of the landscape with a distinct disconnect from the outside world, and you find yourself in a treacherous, high-risk setup. Everything done on this island is multiplied by a degree of heaviness and intensity.

As Bruno so eloquently told the crew after a session one day, “Doctors should put heart monitors on surfers who paddle out here! It is not soft!”

The other side of the island is no different. Most places, even in the outer reaches of the Pacific Ocean, attract certain directions of storms – swells coming up from New Zealand, or down from Mexico – but not here. This particular location gets hammered by almost every high and low that travels through any part of the Pacific.

“It only becomes surfable when the wind has some form of north in it,” says Ted. “We got that on two or three occasions throughout our trip, but some days were just too much – 15-foot grinding death pits. The whole island was almost like a smorgasbord of choices – only the choice isn’t which wave you want to get barrelled on – it’s which wave you want to kill you. It’s bigger than Tahiti here and it gets one of the most direct hits of swells in the world.”

That’s actually how Ted found this place – on Google Earth, just following where the swell goes, and who gets the brunt. Perhaps that is why this island, this place, is so untouched – because we’ve only had the technology and ability to follow swells that acutely, for a relatively short period of time.

“I’ve been researching swells for well over 30 years,” says Ted. “But since swell maps have come into the picture, we’re finally able to actually track swells until they disappear altogether. Previously you’d have to look at a synoptic chart, and usually only apply it to the places you knew – Indonesia or Tahiti, or somewhere along those lines. We never seemed to follow those swells and find out where they went after they hit those spots.

“So now it’s much clearer around the world, and I think this accounts for a lot of the reason why there are so many people going off the edge these days, moving away from the traditional areas – to places that bear the brunt of swells. Where you go, ‘Oh my god, this little volcanic outcrop is in complete line with some of the heaviest swells in existence!’ There is a whole series of islands that just continually gets smashed by swells, and then it’s just a matter of timing it to coincide with optimum winds. It’s all very cyclical, but it’s trying to find that perfect combination. Forecasting has improved so much now that a raid can be such a high chance of getting it right, with really short notice – just like this trip.”

After every journey, it’s inevitable that you look back and compare your preconceived notions about the waves and the culture and the place with the actuality of what you found – where your expectations were met, and where the reality fell short.

Ted touches on this…

“It’s funny. I was talking about expectations, but very rarely do they get met or exceeded. This was one of those rare cases. There’s something about surfing in an environment that’s steeped in culture and richness – it adds an entirely new element to a trip. You get this feeling that it’s more than just waves – it’s a sense of place, of culture. It’s an awesome thing in its energy and scale, and that is definitely translated into the ocean.”

Strong offshore winds. Steep, jagged cliffsides. Reeling, 12-foot slabs. A powerful and unknown ocean. A herd of white horses standing on the hardened volcanic lava above. No signs. No landmarks. Just raw elements. This is where the team found themselves, and it’s the environment that shaped the culture of the place they temporarily inhabited.

“We’d come in to the shore and the wife of the local guy would cook up a BBQ. We’d sit on the rocks eating fish until the sun went down, sometimes without even saying a word. It was such a nice scene and it was genuine. It was moments like that that created the magic of the place – the juxtaposition between the harsh elements and the people who survive in them.”

It doesn’t really happen like this anymore. These days everything is a catered-for experience. You pre-pay for a boat trip. You check in and your bags are transferred. You’re brought to your layover hotel and you get your welcome drink filled with cheap alcohol. You wake up and you get transferred onto a boat where you’re fed for 12 days. You’re dropped off at breaks and you get your photos off the photographer and you know exactly what you’re going to get the entire time you’re away.

“That’s not what this was. This was a journey. A real journey. And in my humble opinion, that ideal is endangered.”

Everyone that has travelled, everyone that has surfed – they know that the whole thing is really about the journey. Perhaps that’s why a trip like this… to an island in the middle of the Pacific, on a volcanic rock, getting bludgeoned by massive swells, as remote, as you can get… is so important.

It’s keeping the Search alive, from the rugged ends of the earth.